May 15, 2014

May Topic Analysis

By Christian Chessman

Resolved: Minimum wage laws benefit the United States economy

The NCFL always has interesting topics, and this one is no different. I think the core subject of the resolution – the minimum wage – is timely, interesting, and academically rich as a subject for debate. The literature surrounding the minimum wage will be educational for most debaters, and may resonate with the personal situations many debaters find themselves in. Understanding both the common arguments and economic nuances of this debate will equip debaters with the tools to participate broadly in public discussions of the minimum wage.

Defining Minimum Wage

What is the minimum wage?

Three important considerations when defining it:

- It's a floor. The minimum wage is the base payment per hour that employers can pay employees. It's important to note that this rate is a floor, not a ceiling – employers can voluntarily choose to pay employees more than the minimum wage, but cannot pay less than it.

- It's statutorily set. The minimum wage is determined by a series of local, state, and federal laws which set an hourly rate. The present federal minimum wage is $7.25, though many states choose to set a higher base minimum wage.

- The highest set wage matters. In practical terms, states may not set a minimum wage lower than the federal wage since companies which paid such a lower wage would still be subject to prosecution for violating federal laws, if not state laws. In that same vein, when states set a minimum wage which is higher than the federal minimum, companies operating in areas governed by those state laws have to pay the higher amount. For example, the minimum wage in the state I live in – Florida – is $7.93 per hour. If a company operating in Florida paid the federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour, they would be fine in federal terms but could be sued for violating state laws. As such, companies must pay the highest minimum wage legally set for the areas in which they operate.

How much should it be?

One common criticism of the minimum wage as a concept is that it's to draw a brightline for what the minimum wage should be since – in the view of critics – any number is necessarily an arbitrary. The argument usually sounds something like this: "If the minimum wage should be 10 dollars per hour, why not 10.01? Or 10.50? Or 15? Or 100?"

Those critics haven't met economists.

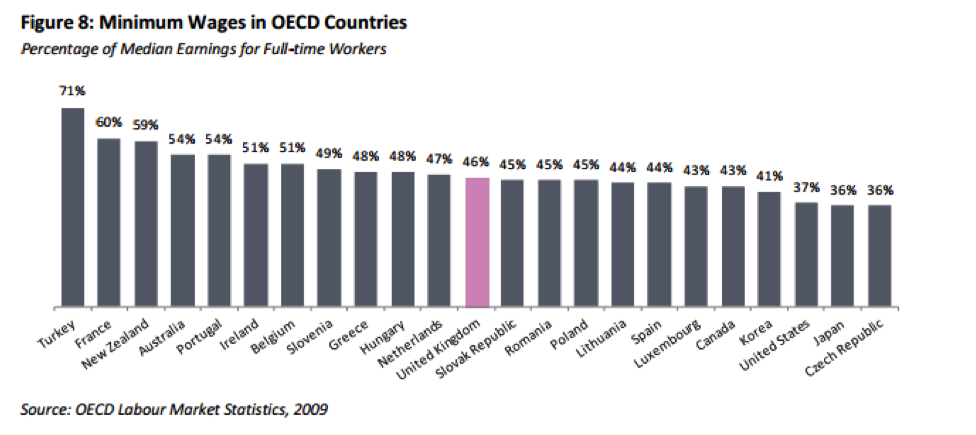

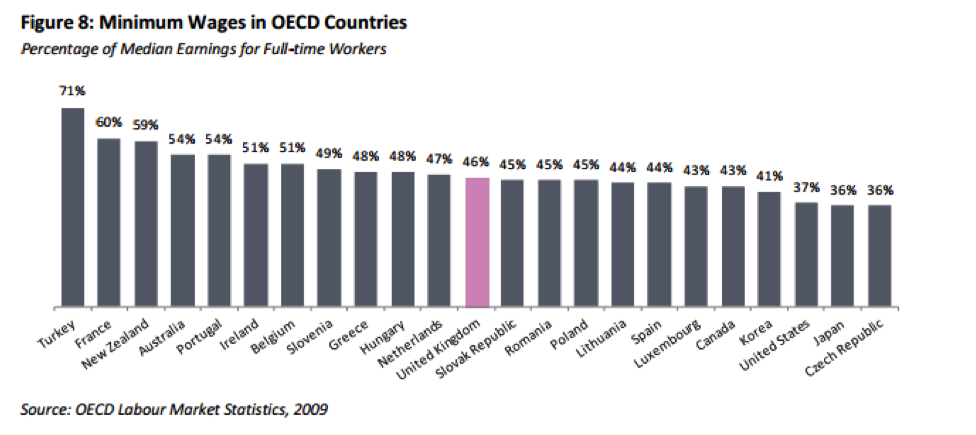

Scholars at the London School of Economics have created an objective way to measure and establish the minimum wage: by determining it in relation to the average salary of the country (or state) in question. These economists look at the median salary in the nation1 and then set the minimum wage as a percentage of that wage. The government can be more or less egalitarian by setting the minimum wage at a higher percentage, making the basic wage closer to the average wage.

As you can see from the below graph, the US is on the lower end of the egalitarian scale – the minimum wage in the US is only 37% of the average wave2.

(Note: The UK is highlighted because this graph comes from the London School of Economics.)

Almost every other post-industrial country has a higher rate than the United States, demonstrating in a preliminary way that it is both possible to set an objective minimum wage and that the minimum wage in the US can be objectively measured and compared to global standards3.

Who makes the minimum wage?

A quick fact summary:

· About 4.4 million Americans earn the federal minimum wage4

· That's 3.4 percent of the workforce5

· Most minimum wage earners are adults6

· 60 percent of them are women7

· The majority (66 percent) of minimum wage workers are employed by large corporationswith over 100 employees8

Defining "Minimum Wage Laws"

The phrasing of the topic's subject ("minimum wage laws") is itself ambiguous. It's unclear if the topic framers meant "current minimum wage laws", "proposed new minimum wage laws", domestic "minimum wage laws" generally, or "minimum wage laws" as a component of the global economic structure.

Since I think there are major problems with each of the interpretations (because I think the topic's phrasing is poor) I'm going to outline the relative pros and cons of each and let debaters choose which they would like to advance in their case.

It's worth noting that whatever interpretation debaters defend, they don't have to defend a "single" minimum wage amount. Debaters could comfortably argue that minimum wages can vary depending on the cost of living in a particular area, or vary in a staggered way based on age demographic. Both have support in the literature9.

Option 1: Current Minimum Wage Laws

The benefit of this version is that it's relatively intuitive as an interpretation, and there's a substantial amount of literature defending and attacking the current minimum wage. It's also most grammatically correct; because the term "benefit" is in the present tense, it suggests that the subject of the verb ("minimum wage laws") should also be interpreted in the present tense.

So far, so good right?

The only problem is that makes the topic bidirectional. Bidirectional is a term from Policy Debate that – in this context – means "opposite advocacies can both serve to negate the resolution". For example, the neg could take the standard route and advocate a libertarian free market approach to wages, claiming that no minimum wage should be set. That seems to negate the topic pretty clearly. However, the negative could also claim that the minimum wage is too low to benefit the economy, and advocate for a higher minimum wage. If the negative merely must attack the present set of laws, then advocating higher or lower wages disproves both the resolution and the aff.

I'm not sure how common this interpretation will be, but it functionally makes the aff impossible. Most of the developing negative literature about the current minimum wage either advocates a slightly higher minimum wage (as opposed to a drastically higher one) or no minimum wage at all. Nearly nobody argues that the 7.25 federal minimum wage is the appropriate wage. Nor does anyone justify the collection of individually set state minimum wages that meet or exceed the federal minimum wage. Both competitive fairness and the degree to which literature reflects the debates support avoiding this interpretation.

Option 2: Proposed New Minimum Wage Laws

The upside of this interpretation is that it is most timely – almost all of the literature discussing the minimum wage discusses it in relation to the increase to $10.10 proposed by President Obama. The specificity of those proposals it also an upside, because it lets debaters take the discussion out of the abstract and into specific analysis and application. This interpretation allows debaters to analyze specific proposals now in the context of economic conditions now.

The downside is in the details. Defining which proposals for minimum wage laws are relevant is complicated; there's the president's proposed wage; the proposed wages of various think tanks; proposed decreases and even abolition among libertarians and far-right economic conservatives. Such an interpretation is likely to devolve into debates over "which new laws" are up for grabs – which also bites the problem outlined in the first interpretation. This interpretation permits affirmative teams to select "new laws which lower the minimum wage" or "new laws which raise the minimum wage". This interpretation has all of the disadvantages of the previous interpretation, with an added element of unpredictability that hurts clash.

Option 3: Domestic Minimum Wage Laws

The third way this topic could be interpreted is as a general economic theory question. In other words, the topic is truly asking the question "Should the US have minimum wage laws at all?". The affirmative is required to prove that a world with some minimum wage laws – whatever they may be – is better than a world without minimum wage laws.

Debates on this topic primarily focus on the benefits or harms of an unregulated market ("free market" if you're neg) when compared to levels of state and federal regulation.

The biggest upside of this interpretation is that it's simple and intuitive. Both the affirmative and negative have a solid literature base (the aff has minimum wage activists and the neg has the whole CATO institute), which means debates are most likely to actually be about the minimum wage instead of debating about the terminology of the resolution.

There are two main downsides to this interpretation. The first is that it's grammatically incorrect - the term "benefit" is in the present tense, and the absence of a modal auxiliary verb (like "would" – compare "would benefit" to "[do] benefit") means the resolution is grammatically not hypothetical or theoretical. I don't know how much this matters in front of most judges you'll get at NCFLs, but if you're going to run this interpretation, I'd have a good justification of it.

The second main disadvantage is that the negative literature sucks. The position "there should be no minimum wage" is not one held by the majority of economists; debate is usually about how much the minimum wage should be, and how rapidly (or slowly) it should be increased. Extremists who cling to the full abolition argument tend to be hyperbolic and ideological. While that's admittedly true of most debate literature, it's especially true of this literature. The substance of these theoretical debates is a bad combination of too generic and too technical at the same time. In the former sense, there's no literature statistically analyzing hypotheticals like this – all the specific analysis is about present or past minimum wage laws. At the same time, the deep theory debates between economists are way too complicated to explain in four minutes, let alone to analyze and compare. Concepts like monopsony, demand inflection points, and divergent theoretical frameworks for analyzing the health of the economy are very dense.

Despite these disadvantages, I would likely write a case with this interpretation. I would also likely include statistical analyses as illustrative examples of the minimum wage working, rather than specific or concrete proposals for a minimum wage.

Option 4: Global Minimum Wage Laws

The resolution doesn't ascribe ownership to the minimum wage laws it references. Seriously. It only states that they must benefit the US economy. There's a substantial literature on minimum wage laws in France and Britain, and how those improve their economies (and thus the US's economy through economic ties). That ostensibly would prove the resolution, because it shows that "minimum wage laws benefit the US economy".

An aff debater could even go so far as to argue that France and Britain's type of minimum wage system (which is different than the US system which uses large increases sporadically; Britain's is annually changed and France's changes quarterly within the year) causes outsourcing to the US. If Britain and France's minimum wage laws cause them to send jobs to America…well…that proves the aff too.

That aff would probably have to win that the outsourcing claim is unique to the other countries, otherwise a smart neg would concede outsourcing and argue that domestic minimum wages also cause outsourcing and a net loss of jobs.

The downside to this interpretation is that it doesn't pass the gut check. A substantial amount of debate with this aff will be confusing, messy and frustrating for all parties involved, and likely confuse the judges as much as your opponent. It's likely that any evidentiary support would also be tenuous, and require stretching to barely make argumentative ends meet.

Nonetheless, if I were negating this topic, I would have at least a preliminary strategy planned out for responding to these affirmatives – just in case. No reason to lose to a squirrely aff.

Impact Framing – The Role of Economic Theory

There are three main economic impact areas that the literature surrounding this topic discusses; job numbers, consumer spending, and the impact both on business generally and small businesses specifically. The relationship between those areas and the minimum wage is complicated, multifaceted, and hotly debated. Unlike other topics, this topic is unlikely to be one which boils down to "my impact is bigger than your impact", since the topic has one singular terminal impact (the economy) and the three impact areas are all interrelated at a basic conceptual level. It's impossible to discuss job numbers without discussing consumer spending (which itself is affected by the health and status of small businesses), which makes it impossible to separate the economic impact areas and then claim "we outweigh".

Since debates on this topic are unlikely to be won at the impact level, they must be won at the link level. Winning debates on this topic – be they affirmative or negative – will primarily be about winning the characterization of the relationship between the minimum wage and the economic impact area. The most effective teams will go beyond mere regurgitation of statistics and explain the theory that underlies those statistics – in other words, why the minimum wage affects the economy in a certain manner is likely to have more gravity in round than studies which simply state that the minimum wage has an effect. Bearing that in mind, this topic analysis will discuss affirmative and negative arguments in a holistic way to incorporate both economic theory and statistics.

Aff Arguments

Stimulus Spending

The strongest affirmative argument relies on the economic benefits created by consumer spending. Higher minimum wages gives a huge subset of workers more money to spend, which stimulates growth.

Jordan Weissman explains how economists can "suggest a link between a higher-wage floor and job creation"10:

There are a few potential explanations. But the one we care about today frames the minimum wage as a kind of economic stimulus. The key is that poor and middle class families tend to spend more of their income than the wealthy, since they're often struggling to meet basic needs. So by taking money from businesses and giving it to their worst paid employees, raising the minimum wage might, in theory, increase consumer spending—which in turn boosts the economy and creates jobs. Let's translate that into the real world for a moment. If you give a McDonald's franchise owner an extra dollar, they might save it. But if you give a McDonald's cashier an extra dollar, they're almost certainly going to spend it quickly, like the next time they go to buy groceries. Since the U.S. is fueled by consumer spending, we're all better off it that money gets used to purchase some milk and eggs than if it gets stuffed in a bank account.

Weissman isn't being hyperbolic when s/he claims the US economy is fueled by consumer spending – it's the single biggest contributor to growth. Consumer spending "accounts for approximately 70 percent of all economic growth", making it safe to say "[t]he U.S. economy is predominantly driven by consumer spending"11. Consumer spending also contributes positively to other major sources of growth, including capital spending12, increased stock values13, and even more jobs14.

In fact, one study found that there's a linear relationship between the "added buying power" from the minimum wage and the total number of jobs15. It argues that "the minimum wage would add jobs to the overall economy because it shifts money from a sector that hoards cash (corporate profits) to a sector that spends it (low-wage workers)" and finds that "for every dollar per hour wage increase", new spending "would stimulate the creation of about 50,000 non-minimum wage jobs"16.

Structural Spending Changes: Debt vs Consumption

That added buying power not only changes the amount of money available for spending, but it also changes the type of spending low wage workers are doing. ___ notes that consumers behave according to one of two spending patterns; public good spending, and debt spending. When consumers have money to spare, they distribute that money into the economy; they go to movies, buy new furniture, take vacations, and generally pay money to businesses that are going to reinvest it back into the economy (either by selling more goods, opening new stores, hiring new staff, or all three).

Growing debt levels disrupt public good spending, though. Instead of spending money on goods, "indebtedness has prompted some consumers to save more of their income to pay down debt, while forcing many others to default on loans."17. As low-wage consumers have less income, they spend an increasingly large percentage of their wages on paying down debt to large lending institutions. As noted above, these financial institutions tend to hoard cash rather than reinvesting it into the economy. Resultantly, each dollar spent on debt has less of an economic return than a dollar spent on public goods.

That comparative loss has a huge potential impact on the economy; "if consumers are to continue to drive the economy, they must be in a sound financial position; if they become overburdened with debt, they are not able to maintain their position as the primary driver of economic growth"18. The weight and "pressure of stagnant wages and mounds of debt" can "hold back the momentum in sales growth"19. In fact, there is an empirical relationship which shows that as the amount of total household debt increases (measured as a percentage of total household income), total public good spending decreases.

Debt spending can be dangerous because it leaves the economy in a highly vulnerable state20:

[W]hen an economy has too much debt, it becomes susceptible to the following chain of events. An event occurs which creates a "mild gloom that shocks the conscience." In other words, a news event occurs which lowers consumer confidence, leading investors to sell assets to start to pay off debt. As asset prices fall, investor confidence is lowered further as others see the value of their investments drop. This leads to further selling, lowering prices further. At some point, consumer's net worth drops to a point where they slow down their purchases, lowering business profits, which eventually leads to lay-offs, further exacerbating the downward cycle.

In short, debt spending creates the potential for negative economic feedback spirals that lead to economic recession and potential crash. If consumers fail to spend enough on public goods because their limited capital forces them to pay down debt, the US economy risks returning to "a deep recession"21. To the extent that a higher minimum wage gives consumers more money to spend, it is the foundation for the single biggest economic driver in the American economy.

In fact, the existence of a minimum wage leads to "a significant boost in incomes for the worst off in the bottom 30th percent of income, while having no impact on the median household"22. This has historically been the case; the consensus among economists is that "the minimum wage ‘substantially ‘held up' the lower tail of the U.S. earnings distribution' through the late 1970s"23.

The above graphic demonstrates how the minimum wage gives the bottom 30% of the US income bracket the ability to consume at a substantially higher rate than they would have otherwise. It's important to note that this effect is statistically attributable to the minimum wage, because the effect grew less strong as "the real value of the minimum wage fell in subsequent decades"24. As the minimum wage stayed stagnant, while inflation and the cost of living increased, consumers were less able to spend on public goods – this relationship "gives us an empirical handle on how the minimum wage would help deal with both insufficient low-end wages and inequality, and the results are striking"25.

In sum, minimum wage laws have two positive effects in terms of consumer spending; the first is to directly increase spending and the positive externalities that result from it. The second is to shift the type of spending away from debt spending, which makes the US economy more resilient and less susceptible to negative feedback spirals.

Jobs

The statistical literature surrounding the minimum wage and jobs is thorough, detailed, and engaging to read. Because jobs have such a powerful symbolic status in American culture, both opponents and defenders of the minimum wage turn to quantitative science to justify their stance on jobs.

The most famous study – and the most robust study in the history of the discipline – on the topic was performed by two economists – Princeton's Alan Kreuger and Berkeley's David Card. They "surveyed 410 fast-food restaurants in New Jersey, which raised its minimum wage from $4.25 to $5.05, and eastern Pennsylvania, which kept its state minimum wage at $4.25"26. They note that while conventional wisdom predicts a loss of jobs, their study found the opposite. Instead, "New Jersey's 19% minimum wage hike" led to "no job loss" and "relative to eastern Pennsylvania, fast-food jobs increased slightly"27.

Though the Card and Kreuger study has its critics, its conclusions have largely stood the test of time. A literature review by the University of Minnesota confirms the Card and Kreuger's findings, noting that "no study has found notable job loss" despite "thirty years of state and federal minimum increases"28. This is true both as a general phenomena and a service sector specific problem. The Minnesota study found that the consensus of the literature was that "[e]ven in the most vulnerable sectors, such as fast food restaurants, employment effects are positive or neutral"29. In case you were worried that Michigan's review wasn't thorough, seven Nobel Prize winning economists made exactly the same claim at the start of this year. Their open letter indicates that30:

"the weight of evidence now show[s] that increases in the minimum wage have had little or no negative effect on the employment of minimum-wage workers, even during times of weakness in the labor market."

In cases where specific studies conflict, affirmative debaters should emphasize that the trend found predominantly by the discipline favors the affirmative. While its true that different methods or different data may produce different results, the astonishing consistency in finding no job losses is reason to err on the side of discarding outliers. This type of argument may give aff debaters an edge when the debate boils down to study versus study.

The theoretical reasons justifying the "neutral or positive" perspective are diverse, though some are complicated. One of the most persuasive is that demand for labor (i.e., jobs available) is inelastic. Elasticity is an economic concept which measures the degree of responsiveness in one economic variable based on change in another31.

For the sake of brevity, I won't explain the concept of elasticity in detail – but debaters who are interested in learning more about this argument should read visit this link to get a better grasp on the concept32. The simple version is that when something is elastic, its sales are highly dependent on price – think of luxury goods, like candy in the checkout aisle of Publix, which you're more likely to buy when they cost 50 cents instead of three dollars. In contrast, when something is inelastic, its sales remain largely unchanged by price – think of basic necessities, like food. For example, most consumers are willing to buy meat, regardless of whether it costs 7 dollars or 10 dollars or 13 dollars.

The resistance to change isn't absolute - raising the price of meat to 1,000 dollars would certainly decrease consumption. That is why economists develop models to measure how resistant or respondent a particular thing (in this case, demand for labor) is to its cost. If demand for labor is elastic, we can expect that that changes in the minimum wage will matter significantly. If labor is inelastic, then the minimum wage increases shouldn't change the number of jobs since it is less responsive to cost.

The literature consensus is that labor is inelastic. A meta-analysis of 53 different elasticity measures established by statistical analysis found that the average elasticity was -.20, which indicates a moderate resistance to price change33. It also indicates the existence of an economic "sweet spot" determining the optimal minimum wage34. $100 per hour is too much, and $7 per hour is too little – and the optimal amount is somewhere in between. That amount is not determined by guesswork, but a sector-specific formula that looks at labor elasticity, average wage, and several other factors. In short, the negative elasticity proves as a matter of economic theory that it is possible to establish a minimum wage that does not kill jobs.

While that wage is low enough to avoid tripping up job numbers, its also high enough to meaningfully decrease poverty rates. The United Kingdom, who annually recalibrates their national minimum wage based on a formula similar to the one cited above, empirically demonstrates that post-industrial, Western countries can prosper with a minimum wage. Because Britain changes their minimum wage annually, they also have more data to analyze than the US, since the US changes its minimum wage sporadically. That increased data provides an important empirical insight that can be used to make conclusions about the US35:

No evidence exists of negative impacts on employment or hours strong enough to worry us about the negative effects of the minimum wage on overall employment income balancing out positive effects. Of course, one might not be surprised by this conclusion if one thinks that the minimum wage has been set at such a low level as to have no impact at all. But this is not the case – there do seem to be sizeable effects on wage inequality.

Data from the United Kingdom are generally supportive of the minimum wage, and should be effectively used when questions of empirical support are central issues in the round36. Here's another US specific study that draws similar conclusions37.

Where does the money come from?

The common jobs objection to the minimum wage is that employers must cut employment for some to pay higher wages for others. If the above evidence is correct, and job numbers are not threatened by a minimum wage, then where does the extra money come from?

One answer is that a minimum wage increases revenue. Employee productivity rates increase when they are happy with their jobs, and relieved of the psychological burdens of poverty38. As a result, their productivity increases with their wage. As wage per employee increases, so does output per employee which suggests businesses balance out their increased expenses with increased revenue. Employee productivity may also increase for reasons other than morale – higher employer standards39:

An increase in the minimum wage may lead employers to encourage employees to work harder, since they're now being paid more. Such an adjustment may be preferable to "cutting employment (or hours) because employer actions that reduce employment can ‘hurt morale and engender retaliation.'" A review of 81 fast-food restaurants in Georgia and Alabama found that "90 percent of managers indicated that they planned to respond to the minimum-wage increase with increased performance standards such as ‘requiring a better attendance and on-time record, faster and more proficient performance of job duties, taking on additional tasks, and faster termination of poor performers.'

Another answer is that a minimum wage decreases costs. When employees are paid well for their work, they have an incentive to remain in their job instead of quitting. Higher employee retention and lower business turnover rates saves money both on lost productivity (while the position is vacant) and on retraining (to prepare the new employee for work)40.

A third answer is increasing the price of sold goods and services. Negative authors tend to object that this simply reinforces poverty because people make more but are paying more as well. This objection is empirically untrue, though, because price costs tend to be marginal in comparison to wage gains. As noted earlier in the topic analysis, most minimum wage employees are employed by large companies – think McDonalds, Walmart and the like. These companies have such a massive scale of production that the costs disperse to nearly nothing.

A study examined price increases in major corporations in response to minimum wage increases, and found that if the US were to increase its minimum wage by 40% (to President Obama's proposed $10.10 per hour), the average cost of a good would increase by exactly one penny for businesses "across the board"41. Even in particularly vulnerable industries, like the restaurant industry, cost increases have been minimal. A study examining US historical price increases found that "previous minimum wage hikes have caused restaurant prices to rise by less than 1 percent"42. In other words, a ten dollar dinner increases by a dime to 10.10.

Other answers included businesses accepting relative profit reductions, lowering executive salaries (about 50 dollars each, or .4% of the average upper-bracket income)43, lowering employee hours without firing them, and organizational restructuring44.

The "B" Stands for Bullsh–…Baloney

There is one major recent study conducted by the Congressional Budget Office which estimated that an increased minimum wage could eliminate jobs. I would be remiss in this topic analysis if I didn't provide solid 2AC answers to the CBO study.

The first answer is that the CBO study uses highly flawed, theoretical economic models that contradict empirical data45. When the analysis is consistent with economic data, the economic consensus is that there are no job losses46.

Second, the CBO study is a glorified guess: "Even CBO concedes that the number of jobs lost could be as low as zero"47. The range of 0 to 1 million potential lost jobs is an insanely large margin of error, and evidence that the study is fundamentally guesswork rather than sound analysis.

Third, the CBO study assumes drastic increases in minimum wage. The study's projection assumed that the minimum wage was raised to 139% its current amount in one sitting. If the US increased the minimum wage moderately, or did so incrementally on an annual basis like the UK does, then the CBO admits its study is wholly irrelevant48.

Weighing

An excellent article explains the way affirmative debaters can weigh affirmative benefits against negative job critiques. Since the weight of the literature is near certain that poverty benefits will result, and near certain that job losses will not result, the judge should err on the side of economic theory trends and vote aff49:

What should people take away from this? The first is that there are significant benefits, whatever the costs. If you look at the economist James Tobin in 1996, for instance, he argues that the "minimum wage always had to be recognized as having good income consequences….I thought in this instance those advantages outweighed the small loss of jobs." Since then there's been substantially more work done arguing that the loss of jobs is smaller or nonexistent, and now we know that the advantages are even better, especially when it comes to boosting incomes of the poorest and reducing extreme poverty.

Booyah.

Negative

The logic for the negative is surprisingly intuitive, especially compared to some of the complicated economic theories. Negative debaters should take advantage of that fact when framing arguments and appeal to the common sense of their judges, while framing the affirmative claims of complicated rationalizations of a simple fact: that the minimum wage hurts the economy.

The authors on the negative are also surprisingly articulate and well-spoken, so this section of the topic analysis will articulate primarily through the literature, rather than paraphrasing it.

Jobs

The CATO Institute lays out the job objection well50:

A fundamental law of economics—the law of demand—states that when the price of anything (including labor) increases, the quantity demanded will decrease, assuming other things affecting demand remain unchanged. In the case of labor, this means as the price of labor (the wage rate) increases, the number of jobs will decrease, other things constant. Moreover, the decrease in employment will be greater in the long run than in the short run, as employers shift to labor-saving methods of production.

This quote captures both important elements of the jobs argument – its short and long term impact. In the short term, as companies scramble to suddenly cover an enormous new cost, they will lay off their employees. In the long term, employers will shift to automated forms of production because machines don't get raises, making the one-time machine purchase substantially cheaper than the ever-increasing pay for minimum wage workers51.

A minimum wage gives businesses an additional incentive to mechanize duties previously held by humans. Most businesses, especially in the manufacturing and retailing area, have many mundane tasks that need to be done, such as running a cash register or tightening a bolt on an assembly line. One of the reasons the manufacturing sector has not been part of the job recovery is that businesses have found it's much cheaper to use machines to do tasks that were previously done by people. Whenever businesses automate any task, they usually must spend a lot of upfront money and time in order to save down the line. Because of the minimum wage, spending the upfront time & money seems more worthwhile. For example, Wal-Mart is in the process of adding automated check-outs to almost all of its stores. Thus, all those cashier jobs will disappear. Imagine what would happen if the minimum wage was raised to $8-10 or more, as some politicians want. Do you think Wal-Mart will be more willing or less willing to add more automated checkouts?

The progressive automation of industry is not always visible to new generations, since many of them are never exposed to jobs lost before their time. The Future of Freedom Foundation reminds us that52:

Years ago, unskilled youth cleaned windshields and checked oil at gas stations, showed people to their seats in movie theaters, and bagged groceries. Many of those kinds of jobs disappeared as the minimum wage rose.

Basic supply and demand theory means that employers will not be able to hire as many employees. Government intervention in the market artificially inflates wages with drastic effects on the economy53.

Wages are not set by fiat, even in the U.S. economy, which is severely distorted by government privileges. Wages, rather, are determined by supply and demand. If the price of unskilled labor rises, why wouldn't employers buy less? No employer could long pay a worker more than the value he produced for the firm. That's why economic theory and empirical observation tell us that an enforced minimum wage destroys jobs, degrades the quality of other jobs, and prevents new jobs from being created.

Employers necessarily respond to higher wages while still trying to maximize business profits – and it comes out of the logical source of funding54:

Many who support the minimum wage argue that somehow, you can raise wages artificially and there will be no effect on employment. But who believes that employers don't respond to higher wages? That's why employers replace workers with machines. That's why they send jobs overseas. That's why manufacturing employment is falling. Why would artificially increasing the wage of low-skilled workers have no effect?

Its true that some jobs cannot be fully automated with technology at present levels of sophistication. For example, automated technical support for computers is still nowhere near as efficient as human technical support, so companies interested in customer service will retain human assistants. In those cases, companies are still unwilling to simply absorb the costs of an increased minimum wage. Instead, they outsource55:

When you force American companies to pay a certain wage, you increase the likelihood that those companies will outsource jobs to foreign workers, where labor is much cheaper. There has been a lot of attention lately on the subject of job "outsourcing", where U.S. companies hire foreign workers instead of Americans. When businesses outsource American jobs, they're not doing it because they hate America; they're doing it because they're trying to cut costs. When you increase the price of labor in America, you create an additional incentive for businesses to hire Canadian, Mexican, or other foreign workers. The best way to stop outsourcing of jobs is to provide the best conditions for doing business in America. A minimum wage just makes things tougher for companies to do business in America. Remember that American companies may have no choice but to outsource with the high cost in the U.S.--they may go out of business entirely if they can't cut costs to a level that's competitive with foreign competitors.

Who do they outsource?

It's true that some minimum wage jobs cannot be effectively outsourced, like cashiers at fast food restaurants. However, there are still substantial numbers of jobs directly vulnerable to outsourcing, including:

· 500,000+ sales jobs56

· 230,000+ technical support jobs57

· 100,000+ production and manufacturing jobs58

· 100,000+ healthcare support jobs59

When employers can't effectively outsource a job or automate it, they turn to an interesting third option: making it an "unpaid internship"60. Though "leading federal and state regulators to worry that more employers are illegally using such internships for free labor"61, there is no effective enforcement mechanism to prevent the exploitation of unpaid interns62:

Many regulators say that violations are widespread, but that it is unusually hard to mount a major enforcement effort because interns are often afraid to file complaints. Many fear they will become known as troublemakers in their chosen field, endangering their chances with a potential future employer.

When the United States last raised the minimum wage in 2009, the number of unpaid internship postings rose 300%63. The actual number of unpaid internships is likely substantially higher, since many unpaid internship positions are circulated through private email listservs, professional and friend networks, and other media which are not publicly accessible.

Does the math match the rhetoric?

Professor Linda Gorman, who taught economics at the Naval Postgraduate School until she became a senior fellow with the Independence Institute, surveyed the literature and found that "Several decades of studies using aggregate time-series data from a variety of countries have found that minimum wage laws reduce employment"64. The relationship between minimum wage increases and job losses is linear and substantial; for every ten percent increase in minimum wage, employment will decrease by about two percent65.

That's true of present proposals for increases in the minimum wage. The Employment Policies Institute analyzed the proposed increase in the minimum wage presented by President Obama and found that it would eliminate "at least 360,000 jobs—and as many as 1,084,000 jobs"66. The Congressional Budget Office has a similar estimate, putting its upper-range estimate for the same proposal at one million job losses67.

Stimulus

Most negative advocates see the jobs question as the controlling question, and frame their attacks on the minimum wage from that starting point. That's true of the negative literature on consumer spending, too.

First, the consumer spending argument relies on the premise that marginal increases in spending from minimum wage are valuable. If job losses occur, though, then the US economy will experience a net loss in consumer spending because some wage is better than no wage. While "[t]he government can promise a higher wage rate, but if a worker loses her job, her income (hourly wage x hours worked) will be zero"68.

Even marginal effects on employment would net decrease consumer spending69:

Others justify the minimum wage saying the employment effects are small. Small? When you lose your job or can't find one, the effect isn't small. It's 100%. So it's nice to give 1.7 million young workers a raise. But what about the 3.4 million unemployed young workers as of last month, workers actively looking for work who can't find it? Is it worth it? Is it worth helping those 1.7 million people if it means making it harder for twice as many people to find any kind of job? That's over 3 million people earning zero. I reject making that tradeoff. It's a bad bargain.

The relatively diminished number of jobs also makes it likely that employers will abuse their employees. That matters to this topic because affirmatives are likely to argue that productivity will increase because of morale, and that turnover will decrease because of increased financial incentives to stay. Neither argument accounts for the increased employer leverage; "the irony of the minimum wage is that it reduces the bargaining power of workers and makes them easier to exploit"70. Indeed71:

"[T]he minimum wage: It "encourages exploitation" of workers by creating a "reserve army of the unemployed," since a legislated minimum creates a labor surplus. Roberts writes, Before the minimum wage, a cruel, selfish employer might have had to mentor his employees or train them or be nice to them despite his nature. Now he won't have to. He can still get workers to work for him. Even more cruelly, the minimum wage encourages workers to exploit themselves. They work harder and put up with more abuse from the boss because the minimum wage reduces the alternatives that are available.

America's economic experience with the minimum wage also suggests that increasing the minimum wage does not net increase the amount of capital consumers have to spend, because business owners compensate for salary increases by cutting benefits. Though the minimum wage increases the amount of money the worker is paid, it does not increase the worker's total financial benefit or expenditure when employers defray those costs by cutting other forms of compensation72.

[M]inimum wage laws may also harm workers by changing how they are compensated. Fringe benefits—such as paid vacation, free room and board, inexpensive insurance, subsidized child care, and on-the-job training—are an important part of the total compensation package for many low-wage workers. When minimum wages rise, employers can control total compensation costs by cutting benefits.

Price increases in response to the minimum wage also prevent the stimulus effect from occurring73:

When wages go up, some businesses raise their prices, which leaves their customers with less to spend elsewhere. So, to some degree, hiking the minimum wage just shuffles money between two different sets of consumers.

It's worth noting that even if the stimulus argument is true; its benefits are fleeting at best precisely for one of the reasons articulated in the affirmative section – debt spending74.

The thing to remember, though, is that even if the minimum-wage-as-stimulus theory is correct, its impact is probably fleeting. In August, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago economists Daniel Aaronson and Eric French produced their own estimate of what would happen if the minimum wage was raised to $10. Even if you factored in price increases and job losses, they found the increase would add $28 billion in spending to the economy. But after about a year, they predict the effect would dissipate. Why? Part of the answer: debt. One reason increasing the minimum wage would plump up spending so much, they find, is that it would give workers the ability to put down payments on big-ticket items like cars. Later on, their spending would fall as they begin making loan payments. "Thus," the researchers conclude, "a minimum wage hike provides stimulus for a year or so, but serves as a drag on the economy beyond that."

A good study on this topic sums both this argument and the negative's position generally75:

Raising the minimum wage increases both the probability that a poor family will escape poverty through higher wages and the probability that another nonpoor family will become poor as minimum wage increases price it out of the labor market. They found that the unemployment caused by minimum wage increases is concentrated among low-income families. This suggests that minimum wage increases generally redistribute income among low-income families rather than moving it from those with high incomes to those with low incomes. The authors found that although some families do benefit, minimum wage increases generally increase the proportion of families that are poor and near-poor. Minimum wage increases also decrease the proportion of families with incomes between one and a half and three times the poverty level, suggesting that they make it more difficult to escape poverty.

The road to ruin is paved with good intentions. Artificial intervention into a complicated economic environment is unlikely to be successful, and very likely to hurt those most in need of protection.

Works Cited

- The LSE uses median for average instead of mean, because mean salaries would not accurately represent the distribution of incomes in the United States. For example, if you have 99 people who make 10,000 dollars and one person who makes 200 million dollars, the mean salary is a little under 3 million dollars (at 2.99 million) and the median salary is 10,000. The latter clearly represents the average income of the population group more accurately.

- Manning, Alan. "Minimum Wage: Maximum Impact" Resolution Foundation. April 2012. http://www.resolutionfoundation.org/media/media/downloads/MinimumWageMaximumImpact.pdf

- Ibid.

- Bingham, Amy. "Fact Checking Michele Bachmann on Minimum Wage". ABC News. June 29, 2011. http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/eliminating-minimum-wage-slash-unemployment/story?id=13951494

- Ibid.

- Center for American Progress. "Raising the Minimum Wage, Rebuilding the Economy". June 7, 2011. http://www.americanprogress.org/events/2011/06/07/17113/raising-the-minimum-wage-rebuilding-the-economy/

- Ibid.

- Garofalo, Pat. "Report: Big Corporations Are Making Huge Profits While Keeping Their Employees Stuck At Minimum Wage". Think Progress. JUly 19, 2012. http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2012/07/19/550991/corporations-profits-minimum-wag/

- Manning, Alan. "Minimum Wage: Maximum Impact" Resolution Foundation. April 2012. http://www.resolutionfoundation.org/media/media/downloads/MinimumWageMaximumImpact.pdf

- Weissman, Jordan. "Would Increasing the Minimum Wage Create Jobs?" The Atlantic. December 30, 2013. http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/12/would-increasing-the-minimum-wage-create-jobs/282577/

- Stewart, Hale. "Consumer Spending and the Economy". The New York Times. September 19, 2010. http://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/09/19/consumer-spending-and-the-economy/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=1

- Capital spending means spending and investment by businesses; contrasted with consumer spending, which is spending by customers. There’s a logical and empirical link between the latter and the former, suggesting that more of the latter leads to more of the former. Chandra, Shobhana. "Consumer Spending Propelled Fourth-Quarter Growth: Economy". Bloomberg. Jan 30, 2014.http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-01-30/economy-in-u-s-grew-3-2-as-consumer-spending-picked-up.html

- Chandra, Shobhana. "Consumer Spending Propelled Fourth-Quarter Growth: Economy". Bloomberg. Jan 30, 2014.http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-01-30/economy-in-u-s-grew-3-2-as-consumer-spending-picked-up.html

- Bingham, Amy. "Fact Checking Michele Bachmann on Minimum Wage". ABC News. June 29, 2011. http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/eliminating-minimum-wage-slash-unemployment/story?id=13951494

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Dougherty, Conor and Holmes, Elizabeth. "Consumer Spending Perks Up Economy". The Wall Street Journal. March 13, 2010. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748703447104575117942059388092

- Bingham, Amy. "Fact Checking Michele Bachmann on Minimum Wage". ABC News. June 29, 2011. http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/eliminating-minimum-wage-slash-unemployment/story?id=13951494

- Dougherty, Conor and Holmes, Elizabeth. "Consumer Spending Perks Up Economy". The Wall Street Journal. March 13, 2010. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748703447104575117942059388092

- Stewart, Hale. "Consumer Spending and the Economy". The New York Times. September 19, 2010. http://fivethirtyeight.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/09/19/consumer-spending-and-the-economy/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=1

- Dougherty, Conor and Holmes, Elizabeth. "Consumer Spending Perks Up Economy". The Wall Street Journal. March 13, 2010. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052748703447104575117942059388092

- Konczal, Mike. "Economists agree: Raising the minimum wage reduces poverty" The Washington Post. January 4, 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2014/01/04/economists-agree-raising-the-minimum-wage-reduces-poverty/?tid=pm_business_pop

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Noah, Timothy. "Why CBO differs from other economists on the minimum wage". MSNBC. February 22, 2014. http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/whos-right-minimum-wage-debate

- Ibid.

- University of Minnesota. "Minimum Wage Q and A". Carlson School of Economics. July 2010. http://www.carlsonschool.umn.edu/labor-education-service/programs-courses/documents/minimum_wage.pdf

- Ibid.

- Coy, Peter. "Seven Nobel Economists Endorse a $10.10 Minimum Wage" Bloomberg. January 14, 2014. http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-01-14/seven-nobel-economists-endorse-10-dot-10-minimum-wage

- Wikipedia. “Elasticity - Economics”. No Date Given. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elasticity_(economics)

- “What is Elasticity?” Sparknotes. No Date Given. http://www.sparknotes.com/economics/micro/elasticity/section1.rhtml

- Konczal, Mike. "Economists agree: Raising the minimum wage reduces poverty" The Washington Post. January 4, 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2014/01/04/economists-agree-raising-the-minimum-wage-reduces-poverty/?tid=pm_business_pop

- Saez, Emmanuel and Lee, David. "OPTIMAL MINIMUM WAGE POLICY IN COMPETITIVE LABOR MARKETS". National Bureau of Economic Research. September 2008. http://www.nber.org/papers/w14320

- Manning, Alan. "Minimum Wage: Maximum Impact" Resolution Foundation. April 2012. http://www.resolutionfoundation.org/media/media/downloads/MinimumWageMaximumImpact.pdf

- The Economist. "What sort of floor?" December 3, 2013. http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2013/12/minimum-wages

- Center for American Progress. "Raising the Minimum Wage, Rebuilding the Economy". June 7, 2011. http://www.americanprogress.org/events/2011/06/07/17113/raising-the-minimum-wage-rebuilding-the-economy/

- Volsky, Igor. "Why Employers Won’t Fire People If We Raise The Minimum Wage To $9". Think Progress. February 14, 2013. http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2013/02/14/1594181/no-firing-minimum-wage-raise/

- Ibid

- The Economist. "The argument in the floor". November 24th, 2012. http://www.economist.com/news/finance-and-economics/21567072-evidence-mounting-moderate-minimum-wages-can-do-more-good-harm

- Covert, Bryce. "A $10.10 Minimum Wage Would Make A DVD At Walmart Cost One Cent More". Think Progress. February 21, 2014. http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2014/02/21/3317901/walmart-minimum-wage-prices/

- University of Minnesota. "Minimum Wage Q and A". Carlson School of Economics. July 2010. http://www.carlsonschool.umn.edu/labor-education-service/programs-courses/documents/minimum_wage.pdf

- Noah, Timothy. "Why CBO differs from other economists on the minimum wage". MSNBC. February 22, 2014. http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/whos-right-minimum-wage-debate

- Metcalf, David. "Why Has the British National Minimum Wage Had Little or No Impact on Employment?" Center for Economic Performance. April 2007. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/19742/1/Why_Has_the_British_National_Minimum_Wage_Had_Little_or_No_Impact_on_Employment.pdf

- Noah, Timothy. "Why CBO differs from other economists on the minimum wage". MSNBC. February 22, 2014. http://www.msnbc.com/msnbc/whos-right-minimum-wage-debate

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Konczal, Mike. "Economists agree: Raising the minimum wage reduces poverty" The Washington Post. January 4, 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2014/01/04/economists-agree-raising-the-minimum-wage-reduces-poverty/?tid=pm_business_pop

- Dorn, James. "Obama’s Minimum Wage Hike: A Case of Zombie Economics". The CATO Institute. February 20, 2013. http://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/obamas-minimum-wage-hike-case-zombie-economics

- Messerli, Joe. "Should the Minimum Wage Be Abolished (i.e. Reduced to $0.00)?" Balanced Politics. November 19, 2011. http://www.balancedpolitics.org/minimum_wage.htm

- Richman, Sheldon. "THE MINIMUM WAGE HARMS THE MOST VULNERABLE". The Future of Freedom Foundation. February 27, 2013. http://fff.org/explore-freedom/article/the-minimum-wage-harms-the-most-vulnerable/

- Ibid.

- Roberts, Russ. "Should we abolish the minimum wage?" Intelligence Squared Debates transcript, reposted at Cafe Hayek. April 4, 2013. http://cafehayek.com/2013/04/should-we-abolish-the-minimum-wage-2.html

- Messerli, Joe. "Should the Minimum Wage Be Abolished (i.e. Reduced to $0.00)?" Balanced Politics. November 19, 2011. http://www.balancedpolitics.org/minimum_wage.htm

- Desilver, Drew. "Who makes minimum wage?" Pew Research Center. July 19, 2013. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/07/19/who-makes-minimum-wage/

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Greenhouse, Steven. "The Unpaid Intern, Legal or Not". The New York Times, Business Section. April 2, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/03/business/03intern.html?pagewanted=all

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Gorman, Linda. "Minimum Wages". Library of Economics and Liberty. 2003. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/MinimumWages.html

- Ibid.

- Coy, Peter. "Seven Nobel Economists Endorse a $10.10 Minimum Wage" Bloomberg. January 14, 2014. http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-01-14/seven-nobel-economists-endorse-10-dot-10-minimum-wage

- Coy, Peter. "The CBO Foresees Lost Jobs From a Higher Minimum Wage". Bloomberg. February 18, 2014. http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2014-02-18/the-cbo-foresees-lost-jobs-from-a-higher-minimum-wage

- Dorn, James. "Obama’s Minimum Wage Hike: A Case of Zombie Economics". The CATO Institute. February 20, 2013. http://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/obamas-minimum-wage-hike-case-zombie-economics

- Roberts, Russ. "Should we abolish the minimum wage?" Intelligence Squared Debates transcript, reposted at Cafe Hayek. April 4, 2013. http://cafehayek.com/2013/04/should-we-abolish-the-minimum-wage-2.html

- Ibid.

- Richman, Sheldon. "THE MINIMUM WAGE HARMS THE MOST